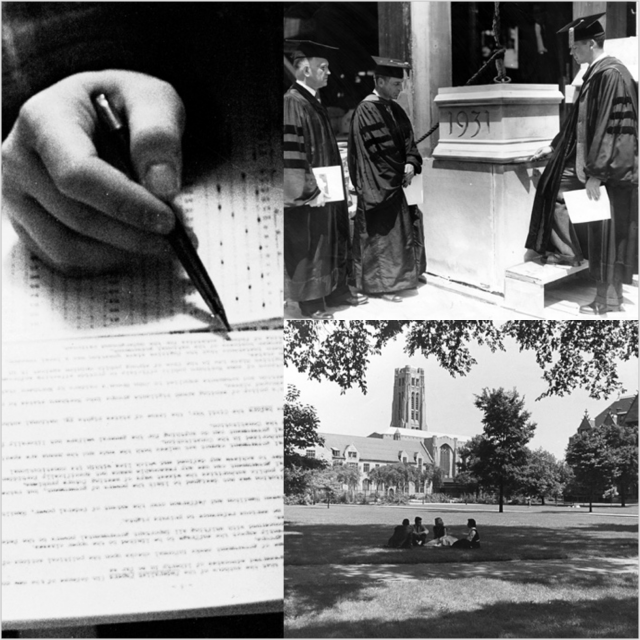

1931-1941

The New Plan

The University of Chicago’s first Core curriculum went into effect in Autumn Quarter of 1931. “The New Plan,” as the curriculum was called, was the product of three years of debate and exploration by Dean Chauncey Boucher and a special committee of University faculty.

The curriculum was comprised of four mandatory, year-long survey courses in the Humanities, Social Sciences, Physical Sciences, and Biological Sciences, each of which consisted of three lectures and one discussion section every week. The grade for each course was determined by a six-hour comprehensive examination administered at the end of the academic year.

The general course in the Biological Sciences included evolution, ecology, botany, human anatomy, and psychology. The course in Physical Sciences included astronomy, chemistry, geology, math, and physics, all in a single class. The course in the Social Sciences had a narrower focus, examining the effects of the industrial revolution on “economic, social, and political institutions.” Readings included Immanuel Kant, Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, Karl Marx, Charles Beard, Franz Boas, Harold Laski, Herbert Hoover, and John Dewey. The general course in the Humanities covered the cultural history of the western world, from Mesopotamia to the 20th century. The course examined one significant text each week, for a total of 30 work in an academic year. Authors covered in the course included Homer, Aristotle, Herodotus, Euripides, Sophocles, Plato, the Bible, Lucretius, Machiavelli, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, and Molière, among others.

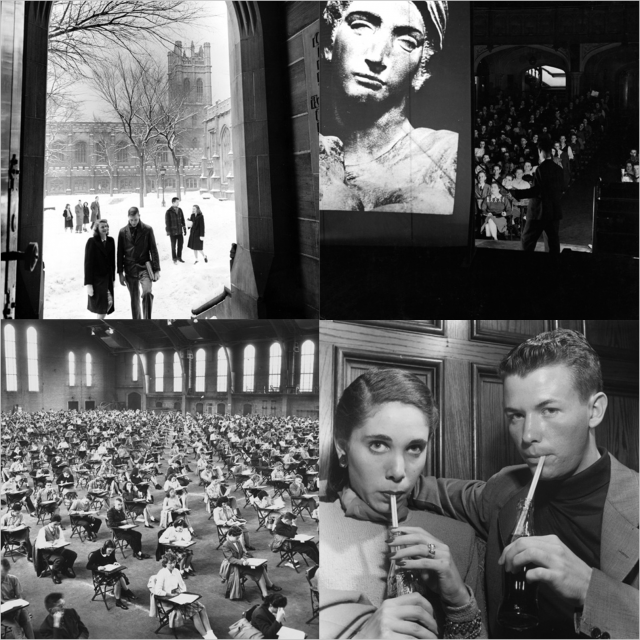

1942-1957

The Hutchins College

President Robert Maynard Hutchins felt the New Plan placed too much emphasis on memorization of facts at the expense of what he called “ideas,” and undertook a massive reimagining of the University’s Core curriculum in January of 1942. This revision entailed some notable changes in how the University approached undergraduate education. First, the 1942 version established a four-year degree program that began in what would usually be 11th grade and ended after the equivalent of the second year of college. Thus, students would now enter college at 16 and graduate at 20. Second, Hutchins’ plan raised the number of required general education sequences from four year-long courses to 14. This change meant that all four years of college at the University would be occupied by these general education sequences, which effectively eliminated the practice of undergraduates majoring in an academic field.

With the 14 required sequences, the weekly workload for each class changed from three lectures and a discussion to two lectures and two discussions, thus shifting the pedagogical approach from largely lecture-based to largely discussion-based. The year-long course in Humanities was expanded into three year-long courses, as was the course in Social Sciences. The courses in Biological and Physical Sciences were replaced with three year-long courses in “natural sciences.” Also added were year-long courses in history, foreign language, math, English, and “OII” (Observation, Interpretation, and Imagination).

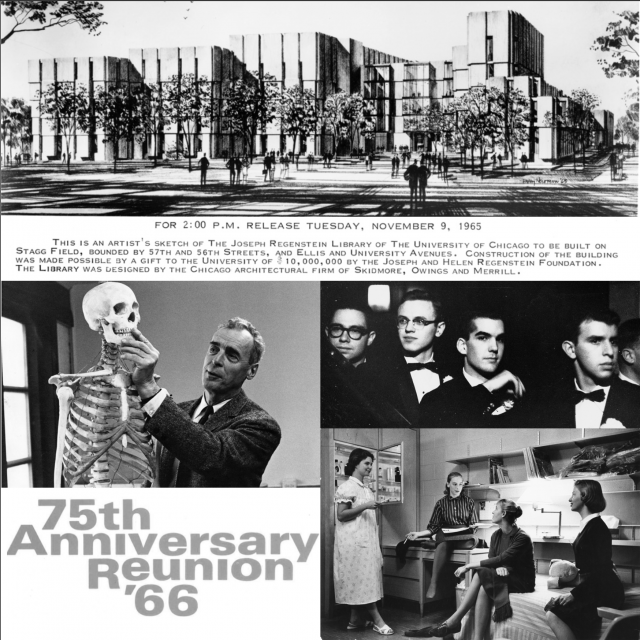

1958-1966

The Counter-Reformation of the 1950s

Throughout the 1950s, Chancellor Lawrence Kimpton undertook a return to the pedagogy favored by the New Plan and introduced measures to undo the changes made by Hutchins. In 1953, the University shifted away from admitting first-year students to begin college after 10th grade and returned to the standard timeline beginning after 12th grade. And in 1958, the University reinstated the traditional practice of undergraduate majors. As a result, the four-year Core had to be reduced. Under the new arrangement, the first two years of undergraduate work would be devoted to Core study, and the second two years would consist of a mix of advanced study within the student’s chosen department and electives.

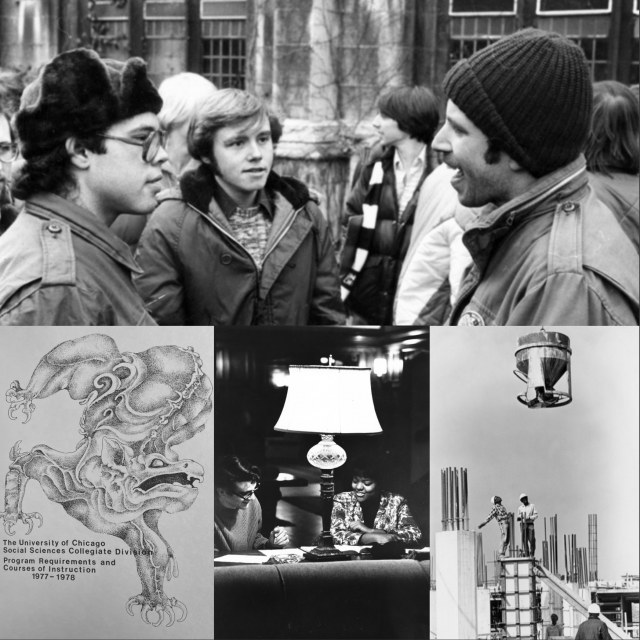

1966-1984

“Division” of Labor

Beginning in the Autumn Quarter of 1966, yet another Core curriculum would take effect. In January of 1966, the University held a week-long conference (classes were cancelled) in which students, alumni, and faculty discussed possible changes to the curriculum. Using input from this conference, a special committee devised a plan for a new curriculum which was approved and implemented that fall.

Under this new plan, there was a “common year” comprised of four year-long general education courses, one each from the Humanities, the Physical Sciences, the Biological Sciences, and the Social Sciences. At least two of these courses had to be taken during the first year. Many of the Core sequences that exist today emerged during this period. The Humanities requirement, for instance, could be fulfilled with Philosophical Perspectives on the Humanities. Likewise, the Social Sciences requirement could be fulfilled with Self, Culture, and Society.

Aside from this common year, responsibility for deciding nearly all the curricular requirements was shifted to the Collegiate Divisions. For instance, there were no universal requirements for undergraduates in foreign language and mathematics. Instead, the Collegiate Division under which the student’s major fell determined these requirements. The Social Sciences Division required - beyond the 12 quarter of common year sequences - six quarters of civilization studies, a three-quarter calculus sequence, foreign language competency, and three electives outside the social sciences. The courses taken by students in the College during this period thus fell into four main groups: the common year, the divisional Core requirements, the major requirements, and electives.

1985-1998

The "Common Core"

In the 1980s, Dean Donald Levine set about another restructuring of undergraduate education in the College. The most significant of these reforms came in 1985. This reorganization removed curriculum-making prerogatives from the Collegiate Divisions and returned to a standardized curriculum common to all students in the College.

Under this plan, undergraduates took 42 courses over the course of four years, 21 of which were general education requirements, with the remaining 21 comprised of a mix of major requirements and electives. This reassembled common Core consisted of seven total quarters in Humanities and Civilization studies, six quarters in Natural Sciences, three each of Social Sciences and Foreign Language, and two in Mathematics.

1999-PRESENT

The Core Today

Under Dean John Boyer’s leadership, the College introduced the most recent reforms to the Core curriculum in Autumn Quarter, 1999. These changes were informed by a large survey of the student body conducted in 1995. Significant portions of the student body - especially those majoring in the natural sciences - felt that the Core curriculum was difficult to manage. The 1999 reforms reduced the size of the Core from 21 classes to a more manageable 18 (or, if language competency was demonstrated via exam, 15). The new, slimmer Core consisted of six quarters total in Humanities, Civilization studies, and Art, three quarters in Social Sciences, three in a Foreign Language, and two each in Biological Sciences, Physical Sciences, and Math. Thus, the undergraduate curriculum was now made up of one-third Core classes, one-third major classes, and one-third electives, which gave third- and fourth-year students greater ability to design their own educational programs.

Though there was much controversy and debate surrounding the perceived ‘softening’ of the Core curriculum among students, faculty, and alumni alike, the reforms themselves, once implemented, were well-received by students. In March of 1999, all students currently in the College were given the option to finish the remainder of their education under the 1985 Core or to switch to the 1999 Core. Ninety-five percent of students chose to switch to the new Core. It was clear that students wanted and appreciated more control over the structure of their studies.

This latest iteration of the Core has proved notably enduring. It has anchored the foundations of general education across the four Collegiate Divisions while fostering a dynamism that allows for innovation and renewal.

For more on the history of the UChicago Core, please see John Boyer’s, A Twentieth-century Cosmos: The New Plan and the Origins of General Education at Chicago.