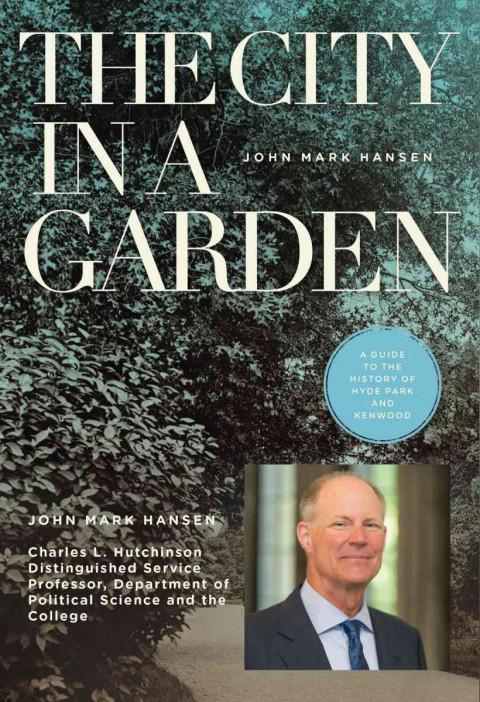

Prof. John Mark Hansen has called Hyde Park home for more than 30 years. In a new book, Hansen, one of the nation’s leading scholars of American politics, traces the origins of the Hyde Park-Kenwood neighborhoods from 1853.

The City in a Garden takes its title from a translation of the city of Chicago’s motto, Urbs in horto, and harkens back to Hyde Park’s roots as a retreat from city life. It also delves into the history of the major parks that surround the neighborhoods: Jackson Park, Washington Park and the Midway Plaisance. Hansen seeks to inspect the “place-ness” of the area by taking inspiration from the individuals who lived there during its development.

An avid cyclist who hosts two annual bike tours with Dean John W. Boyer, Hansen values the block-by-block details of these communities and hopes to inspire a similar appreciation in others. The College sat down with Hansen, the Charles L. Hutchinson Distinguished Service Professor in Political Science and the College, to discuss the new book and his favorite local gems.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How did you get started on this project?

I’m a cyclist, which means I’ve been all over the South Side, and I became curious about the places I was going through.

I gathered a lot of information about the areas north and south of here, and I realized four or five years ago that I had not looked into Hyde Park-Kenwood itself, and that became the beginning of this book.

You are a political scientist, so this is a different space for you to be working in. How did you get interested in the historical approach?

I’ve long been interested in history and the history of this part of the city in particular, so it wasn’t that long of a stretch. Of course, there’s some politics in this book, because in Chicago it’s very difficult to avoid that, and Hyde Park had its own distinctive politics. But I wanted it to be broader than that, in part because I’m also interested in the economic, cultural and social histories and all these different aspects of Hyde Park. I wanted to capture all of the varieties of experiences of people who lived in Hyde Park and Kenwood.

In the preface, you mention that you wanted to capture the experiences of people as individuals, almost by the blocks they lived on. How did this sense of place influence your process?

For the landmarks that are still here, it’s this curiosity: “What is that? What’s the story of that particular bit of architecture or that certain park?” I think that part of the experience of living in a place is physically being in that place. I wanted people to be aware of who the neighbors were, and what were the things that people who lived here 50, or 100, or 150 years ago would have experienced, heard about or participated in.

I really do want to emphasize the “place-ness” of history. Some people just passed through. Some were born, lived and died here. But they’re all part of this area’s history.

When it came to your research process, what kinds of sources were you drawing upon?

The largest source material is from the newspapers: Chicago Tribune, Hyde Park Herald and Chicago Defender. I also used city directories and Census material. A lot of the discoveries were kind of lucky—I stumbled upon one topic while I was looking up another. That included doing research on other parts of the South Side. When it was a village before being incorporated into the city, Hyde Park went from 39th to 138th east of State Street, so it encompassed most of what is now the whole South Side.