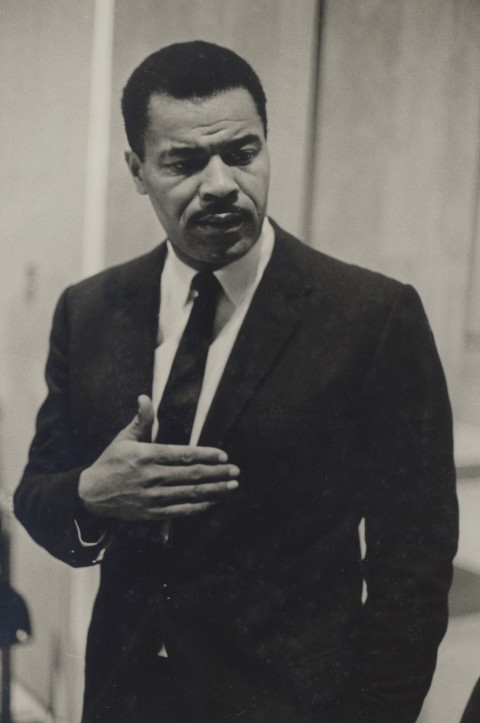

Paul B. Moses was only an art professor in the College for four years before his tragic death in 1966 at the age of 36, but he made a lasting impact in Hyde Park and beyond during that time.

Moses was one of the first prominent Black art historians who boldly spoke out about issues of race at a time when public opinion was largely against him.

Until Dec. 16, visitors can come to the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center at the Regenstein Library and chronologically follow the story of his personal life, academic interests, artworks and his prominence in the art history world and as a professor at UChicago.

To cultivate an intimate feeling in the exhibit, co-curator Stephanie Strother, a fourth-year art history Ph.D. student at UChicago, focused on incorporating small personal details. Special Collections Exhibition Designer Chelsea Kaufman pitched in too, reproducing the header texts and case labels in the exhibit from Moses’ handwriting.

In addition to highlighting Moses’ invitations to lectures on Matisse, his work as an art critic for the Chicago Daily News, and even art of his own, the exhibition’s discussion of Moses’ prominence in the art community highlights the discrimination and suffering he had to undergo as a Black individual in a predominantly white field.

Moses was the first African American student at Haverford College, and was frequently singled out as one of the few Black art historians of the time.

“In photos from art events around Chicago, he is usually the only Black person there,” Strother said. “In the letters we have, he rarely addresses it directly, but of course he was aware.”

At UChicago, Moses is known for his refusal to teach Mark Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn” because of the novel’s portrayal of slavery, a stance for which he faced significant opposition from the academic community at the time.

Despite his vulnerable position as a Black professor, Moses stood up and expressed his discomfort with the novel. This moment even opens the Introduction to literary critic Wayne C. Booth’s “The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction.”

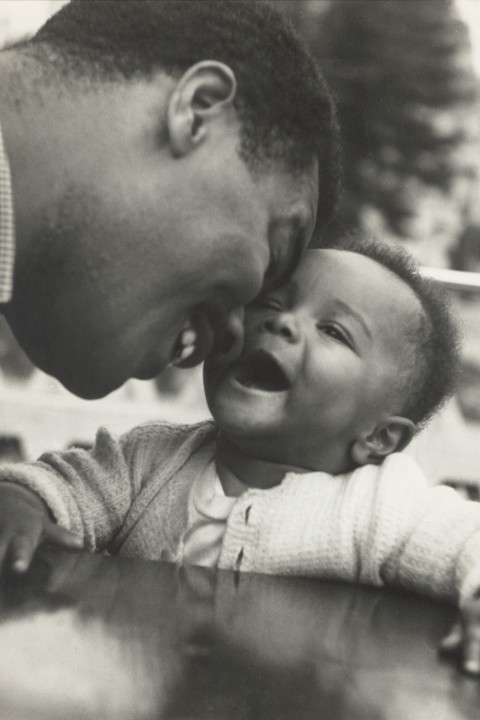

This exhibit also offered a unique opportunity for Strother, to collaborate with a family member of the subject of her exhibition: Paul Moses’ son, Mike Moses, a phys. Ed. teacher and former soccer coach at the UChicago Lab School.

“Working closely with Mike was one of the great joys and pleasures of working on this exhibit,” Strother said. “It reminds you of how little you actually know about the subjects you study, and how irreplaceable the knowledge that comes with being intimate with the subject is.”

Strother and Mike Moses first met by chance on campus while they were both walking their dogs. Mike Moses said that he had no idea what went into creating an art exhibit at the time, but when the two started talking about Mike’s father, Moses and Strother began to think of a way to honor his impact at UChicago.

Moses eventually showed her the boxes of memorabilia about Paul Moses that his mother had saved, and they soon began the process of applying for the Regenstein space and curating the exhibit.

Both curators reflected on the importance of the Regenstein exhibition space, a centralized location that is highly accessible to the UChicago community.

“Where it’s located, there’s so many individuals and so many individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds walking from Regenstein to Mansueto and back,” Mike Moses said. “The exhibit presents a different historical feel that you may not get from a larger museum, and the ease of use not only allows you to learn more, but it’s also more intimate.”